Philip Baum examines our current approach to airport security screening in light of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic and against the backdrop of war in eastern Europe. He proposes a refocus on the content of security training courses and explores the actions that can be taken, especially when the potential use of chemical or biological weapons is clearly present, when concerns are identified but no traditional weapons or explosives are detected.

It’s all too easy, and perhaps even understandable, for us to become distracted from the traditional threats to civil aviation by the horrific events taking place in Ukraine. Wall-to-wall media coverage of the devastation being wrought, and the utter misery caused, by Russia’s military invasion has eclipsed all other news to the extent that even the coronavirus pandemic seems to have been consigned to the history books. The reality, however, is that not only are the pre-pandemic and pre-invasion challenges still with us, the threat we face may well have escalated and our vulnerabilities increased.

Firstly, due to our proclivity to be influenced by primary-recency, within the security industry we can succumb to considering the most recent news we have heard as being indicative of the preeminent threats that we face. To illustrate this, in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks there was considerable fear that the next attack would surely involve terrorists seizing an aircraft and piloting it into a population center in a suicidal mission. Likewise, after the shoe-bomber incident we focused on footwear and after the underpants bomber it was all about what might be concealed in the groin. Small wonder then that we are often accused of being reactive rather than proactive in our development and implementation of countermeasures.

There has been a downturn in the number of Islamist-inspired atrocities in the developed world and there have indeed been very few old-school hijackings of aircraft. Aside from the surge of unruly passenger incidents, often the result of disputes pertaining to the wearing of the mask, most of the attacks against aviation assets have been in conflict zones well away from the Western-centric media’s gaze and of scant interest to those performing screening duties at the world’s major transportation hubs.

There is every reason for concern. We know that the pandemic has afforded an opportunity for radicalization, caused a dramatic increase in mental health-related issues, impacted our employees’ livelihoods — a potential driver for insider attacks — and generated a plethora of justifications for protests related to climate change, concern over infringement of civil liberties and enforced social distancing.

Meanwhile, the Western world’s response to the war in Ukraine has inflamed the resentment felt by certain groups; European countries which have been combating the influx of political and economic refugees from the Middle East and Africa are being accused of hypocrisy and racism as they open their borders to the hundreds of thousands of those fleeing the Russian bombardment. The quantity of online chatter by Islamists exploiting the argument is fueling radicalization and imagery of comparatively small numbers of Black migrants’ boats and dinghies being turned away in the Mediterranean Sea, or English Channel, is being shown in parallel to the stream of white, predominantly Christian, refugees streaming across the borders from a beleaguered Ukraine into refreshingly welcoming European states where nationals are waiting and advertising, placards aloft, to host the victims of war. In the UK, the government has announced that it is planning to pay British householders £350 per month to accommodate Ukrainian refugees for up to six months. Regardless of the concrete justification for these humanitarian responses, we ignore the optics, implications, and the associated rhetoric, at our peril.

As this article goes to press, reports are emerging that 16,000 mercenaries from Syria, and elsewhere in the Middle East, are to make their way to Russia to support their war effort. They are, of course, being welcomed with open arms. In the short term, this may be of little significance to aviation security; longer term, we know from previous global conflicts, that war affords its participants opportunities to acquire weaponry that can be used in subsequent military and paramilitary activities.

Whilst MANPADS falling into the wrong hands might be the industry’s prime concern, given the current situation, it’s chemical, biological and radiological weapons that could prove taxing for us all and become a challenge for those working at airport security checkpoints. I say “could prove,” but perhaps, given an already established modern history of their usage, we should say “are already” and we’ve just chosen to ignore it.

Checkpoint Protocols

In the vast majority of airports around the world, the security checkpoint still consists of an X-ray machine and archway metal detector. Sure, many of the terminals that readers may transit through will also have explosive trace detection technology and computed tomography is in the earliest stages of widespread deployment, but the detection capability of the screening process is still focused on countering the hijacking threat of yesteryear. There is a reluctance to accept that.

Yet a sea change in terms of checkpoint mindset has occurred — but bizarrely solely in relation to the pandemic. We must recognize that, whilst security guards and screeners may remain concerned about the potential for COVID-19 transmission at the checkpoint, they are not there to act as quarantine officers or public health officials. They are employed to identify those with negative intent.

We train people how to operate deployed technologies, but we are reluctant to teach our staff of the limitations of each solution, often due to concern that expressing them might result in sensitive information falling into the wrong hands. For example, are screeners able to identify which groups of explosives cannot be identified by ETD systems? Or do they know what quantity of explosives needs to be present for automated detection?

Knowing what technologies cannot do is as important as knowing what they can do.

Chemical/Biological Weapons

As already mentioned, chemical and biological weapon detection capability is not part of our security apparatus. There is an argument that, until they are utilized in an attack against aviation, the expense of developing and deploying effective countermeasures cannot be justified. The use of sarin in the attack on the Tokyo Metro in Japan in 1980 is regarded as an outlier incident against a different mode of transportation, so of little consequence to airport security screening. The landside assassination of Kim Jong-nam — the half-brother of North Korea’s President Kim Jong-un — at Kuala Lumpur International Airport in 2017 might have involved the use of the VX nerve agent but the incident was also seemingly disconnected from broader international security issues and, whilst it did take place in the public area of an airport, could have taken place in any public space.

The 2018 usage, by Russian agents, of the Novichok nerve agent to try to assassinate Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, in Salisbury, UK, had, on the surface, no industry context — except, of course, how the agent was brought into the United Kingdom in the first place. However, alleged Russian-sponsored attacks have indeed impacted aviation; they are just not the incidents explored in training courses. Whilst shoe bombs and improvised explosive devices concealed in underwear — having been used by Islamists against industry assets — are cited, how many screeners are cognizant of the details of the attempted assassinations of Alexei Navalny and Anna Politkovskaya or the actual assassination of Alexander Litvinenko?

Litvinenko was intentionally contaminated with the radioactive isotope polonium-210 when his assassins introduced the deadly toxic substance to his tea in a London restaurant in 2006. Approximately 700 people were identified as having been exposed to radiation as a result, but from an aviation perspective it is important to note that three British Airways aircraft were identified to have had small traces of polonium-210 on them. In excess of 33,000 passengers had the potential to have been exposed to contamination, let alone the impact to aircrew and ground staff who had serviced the aircraft. Fortunately, there were no further deaths.

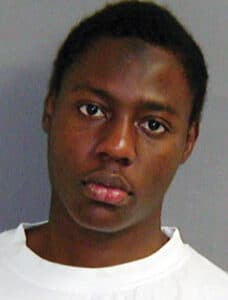

On August 20, 2020, Alexei Navalny, Russia’s opposition leader, was contaminated with Novichok. Navalny fell ill on a domestic S7 Airlines flight from the Siberian city of Tomsk to Moscow. As his health deteriorated, and given that he was screaming in agony, the crew elected to divert to Omsk where he was hospitalized; two days later he was sent to Berlin for specialist treatment. Whilst Navalny was filmed drinking tea at Tomsk Airport prior to boarding his flight, it is believed that he was poisoned at the Xander Hotel he had been staying at in Tomsk; traces of Novichok were found on a bottle from the mini bar in his room.

Albeit that the incident is not a standard case study in most aviation security courses, the Navalny case was headline news around the world. After all, this was Russia’s opposition leader. Less well known is the case of human rights activist and Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya.

U.S.-born Politkovskaya, eventually shot dead in a lift in her apartment block in 2006, had previously been poisoned on an Aeroflot flight from Moscow Vnukovo to Rostov in September 2004; she was traveling to the Caucasus to cover the Beslan school siege. The incident is best described by Politkovskaya herself in an article she wrote for The Guardian newspaper:

“…a man introduces himself as an airport executive: ‘I’ll put you on a flight to Rostov.’ In the minibus, the driver tells me that the Russian security services, the FSB, told him to put me on the Rostov flight. As I board, my eyes meet those of three passengers sitting in a group: malicious eyes, looking at an enemy. But I don’t pay attention. This is the way most FSB people look at me.

“The plane takes off. I ask for a tea. It is many hours by road from Rostov to Beslan and war has taught me that it’s better not to eat. At 21:50 I drink it. At 22:00 I realise that I have to call the air stewardess as I am rapidly losing consciousness. My other memories are scrappy: the stewardess weeps and shouts: ‘We’re landing, hold on!’

“‘Welcome back,’ said a woman bending over me in Rostov regional hospital. The nurse tells me that when they brought me in I was ‘almost hopeless.’ Then she whispers: ‘My dear, they tried to poison you.’ All the tests taken at the airport have been destroyed — on orders ‘from on high’, say the doctors.”

Whilst not a chemical/biological incident, in the context of targeting journalists in-flight, it would be remiss of me not to mention the alleged state-sponsored hijacking to Minsk of a Ryanair flight, en route from Athens to Vilnius on May 23 last year. The crew were ordered to divert to Minsk, despite being closer to the Lithuanian capital, due to a “bomb threat” received whilst it was in the airspace of Belarus. As cited in the January 2022 Report of the ICAO Fact-Finding Investigation:

“According to the Department of Aviation of Belarus, on the 23 May 2021 at 09:25:16 (12:25:16 local) an email was received in the generic mailbox info@airport.by…”, and “The email contained the following text: ‘We, Hamas soldiers, demand that Israel cease fire in the Gaza Strip. We demand that the European Union abandon its support for Israel in this war. We know that the participants of Delphi Economic Forum are returning home on May 23 via flight FR4978. A bomb was planted onto this aircraft. If you don’t meet our demands the bomb will explode on May 23 over Vilnius. Allahu Akbar.’”

On the ground in the capital of Belarus, two of the passengers — Roman Protasevich and his girlfriend, Sofia Sapega — were arrested. Protasevich, a political activist and journalist who was outspoken in his criticism of the Lukashenko regime, had been living in exile in Poland since 2019.

Current political events cannot be divorced from the threat to civil aviation. Now, more than ever, we need our approach to be proactive rather than reactive.

Alarm Resolution

In our alarm-centric world, we need to know how to resolve signals that could indicate the presence of a prohibited or restricted item. Let’s consider a scenario in which a passenger causes the archway metal detector to alarm. Nowadays, the screener can normally identify the approximate level (or location) of the cause and that certainly helps, but divesting additional items from the person (such as jewelry, belts, wallets, coins, watches, etc.), and then asking the passenger to go through the detector an additional time, might not resolve the problem. What next?

The general rule is to resolve the alarm but that is not always possible. Physical body searches are discouraged, especially since the commencement of the coronavirus pandemic. For me — as a proponent of behavioral analysis — resolution does not necessarily mean always identifying the actual product that has caused the alarm. It is possible that certain accessories to clothing or jewelry that simply cannot be removed (such as bangles on an arm) might be the culprit, likewise certain medical implants. The determination as to whether the passenger is a risk to a flight can be achieved through questioning and an appraisal of their appearance and behavior.

The harder question to answer is what one should do when the cause of the alarm is the screener’s gut feeling. Expressing subjective concern does not sit well within our security system. We do encourage the general public to report suspicious behavior, but we are reluctant for our security professionals to determine whether a passenger can board a flight based on their hunch alone.

A security guard who identifies a potentially threatening passenger due to behavioral detection is encouraged to resolve their concerns through the use of technology. They are to report concerns, often through a long chain of command — from agent to team leader, team leader to supervisor, supervisor to duty manager and, maybe eventually, from terminal manager to some representative of local law enforcement — in which the initial concerns witnessed are diluted by the process of Chinese Whispers. And, all too frequently, the decision as to how to process the passenger is based on the answer to the question, “OK, I note your concerns, but did the archway alarm or did you identify anything prohibited or restricted in their baggage under X-ray examination?” If the answer is no, we are reluctant, for fear of potential complaints or civil litigation, to deny the passenger boarding.

The root of the problem is that the aviation security screening process is not designed to identify negative intent; it is all about finding the weapon or threat item. The airport security checkpoint is a moment in time; we even refer to everything beyond the checkpoint as being “sterile” when, in reality, we know that it is, at best, security restricted. We know that many airport-based employees are not subject to the same stringent security checks as passengers. We know that, even in prisons — which have little in the way of commercial pressures, throughput rates to achieve or concerns about customer satisfaction — prohibited weapons and substances are regularly infiltrated. And we also know that our checkpoint technology cannot detect a plethora of different explosive types — especially those which are homemade — or the chemical or biological agents referred to above.

Conclusion

We need to be much cleverer about how we implement security and the level of expertise on the front line needs to be expanded upon. We need to be more honest about our detection capabilities and we also need to enable decision-making based on the perceived threat an individual poses.

If our gut feeling is that an individual poses a threat, we cannot limit ourselves to the technologies currently deployed at the checkpoint. In many an airport, our colleagues working in customs controls have more advanced detection devices at their disposal. Whilst airport security checkpoints equipped with advanced imaging technology utilize millimeter wave-based solutions which can see beneath clothing, customs agencies are prepared to use transmission X-rays capable of enabling the identification of internal carries. Even if one dismisses the probability of body cavity devices being used to target aviation, as with narcotics, the body can easily be used to infiltrate small weaponry, including chemical and biological weapons. We can’t resign ourselves to being incapable of identifying such threats.

If a security guard sees somebody they believe to have suicidal intent, they need to know how to respond — immediately. We can’t just tell them to “report it.” We have to enable and empower them to be first responders, yet few airports provide their staff or contractors with any self-defense training or even stipulate the degree to which physical fitness is a job requirement. Many security managers refuse to incorporate such operational dilemmas in training modules for their staff. They are concerned about anybody taking unilateral action and terrified that, by even suggesting a security guard might have to physically engage a suicidal terrorist, there could be economic consequences; the unions, they fear, would demand higher salaries for staff who are putting their own lives at risk. In reality, we are talking about exceptionally rare instances, but aviation security is, by its very nature, the search for needles in haystacks.

As the world’s geopolitical situation is evolving at pace, we must strive to update our approach to screening. To safeguard the industry, aside from embracing behavioral analysis to address the threats of the future, we must also encourage our staff to think outside the box and remove the fear of retribution for making a call, justified for security purposes, that does not result in a prosecution.

Philip Baum is managing director of Green Light Limited, visiting professor of Aviation Security at Coventry University and chair of Behavioural Analysis 2022 (see www.behaviouralanalysis.com), taking place in Northampton, UK, in June 2022. Philip is the former editor of Aviation Security International and the recipient of the 2021 award for Lifetime Achievement and Contribution to Aviation Security. He can be contacted at editor@avsec.com.