In the days when I used to edit Aviation Security International, I would appeal to contributing writers to avoid commencing their articles with the words ‘Ever since the tragic events of 11th September 2001…” My reasoning was twofold. Firstly, it did become somewhat repetitive. Secondly, it tended to emphasise how focussed we had become on the events of that day, almost to the exclusion of other atrocities which have blighted aviation security history.

Not for a moment do I wish to downplay the significance of the events of twenty years ago; the loss of life in the coordinated attacks is unparalleled and the graphic imagery of commercial aircraft being flown into iconic buildings, combined with the hours of footage from thousands of sources of the aftermath – let alone the military conflict that was to ensue – have etched that date in all our memories. However, by concentrating our attention on the events of that one day – something we can leave to the mainstream media outlets – we run the risk of failing to learn the lessons of the less spectacular events, often devoid of substantive imagery, which have taken place.

Every life stolen prematurely by those with an evil inclination, or indeed due to professional negligence, has equal value. Whilst we rightly mourn the 2,977 lives lost on 9/11, we should also see to it that those less likely to be memorialised by the plethora of US-focussed documentaries are also remembered at this time. After all, 24 January, 22 March, 24 March, 7 May, 28 June, 18 July, 24 August, 31 October and 29 November are just some of the dates on which mass casualty events have taken place, targeting aviation interests, since 2001. The dates just listed may not resonate with all readers. So, with that in mind, I commence…

Ever since the tragic events of 11th September 2001, and certainly long before it, the aviation industry has been grappling with how to safeguard passengers, crew, aircraft and airports from criminal attacks.

Our prime concern has been the terrorist threat as successful attacks driven by political ideology tend to incur a higher casualty rate. There are other more practical reasons why we adopt a counterterrorist stance — our ability to secure funding, ease of visualising the persona of the enemy, and our familiarity with modelling responses based on military experience to name a few. Attacks driven by psychological disorders, usually of a lone individual, can impact any route on any date, with the same degree of concern, but too often these incidents are dismissed as being safety issues. Arguably this is our most significant vulnerability and is exemplified by the fact that our screening process is still driven by the search for explosives and not the identification of negative intent.

The coronavirus pandemic has further blurred the lines between safety and security. As evidenced by the increase in unruly passenger incidents being reported over the last 18 months, often fuelled by the requirement to wear masks in flight, there is a considerable amount of incendiary tension within our aircraft cabins. Poor mental health is impacting upon the behaviour an ever-increasing number of people, many of whom will be our passengers and crew, and, whilst not justifying it, many of those employed in security-restricted zones of airports may also be under increased pressure to facilitate insider acts for pecuniary gain. And, in terms of passenger screening, masks significantly limit our ability to effectively implement behavioural analysis techniques whilst there is also greater pressure on screeners to maintain social distance from many of those passengers with whom they should actually be up close and personal.

If we exclude plots to destroy aircraft identified either by the intelligence services ahead of time or at airports prior to departure, there have only been six attempted bombings of aircraft inflight since 9/11 — the ‘shoe bomber’ (2001), the ‘underpants bomber’ (2009) and the Daallo Airlines bombing (2016), which all failed in their intended missions, whilst all the passengers and crew died aboard the two Russian airliners brought down simultaneously on 24 August 2004, as did those on board the Metrojet flight operating from Sharm el-Sheikh to St. Petersburg in 2015. All flights destroyed were Russian registered aircraft operating to cities in Russia; I am not sure that is reflected within the industry let alone by the media.

In terms of hijackings, there have been around 60 attempted hijackings since 9/11. On those flights there have been a total of five fatalities and all of those were the hijackers themselves. With there being (pre-COVID) almost 40 million flights per year in 2019, this is something we can take considerable pride in.

Pride but not complacency. Aviation security is, after all, a search for needles in haystacks.

Post-9/11 Incidents

Most of the incidents resulting in mass casualties have had nothing to do with traditional airport security screening and were not the result of negligence of either airport personnel or aircrew; they have taken place in the skies over conflict zones.

The first significant loss after 9/11 was the destruction of a Sibir Airlines flight en route from Tel Aviv, Israel to the Russian city of Novosibirsk. 78 people perished when the aircraft was shot down on 4 October 2001 when, according to a report by Professor Jacek Gieras, the “Ukraine defence forces were doing an exercise near the coastal city of Theodosia in the Crimea region. Missiles were fired from an S-200V missile battery. A 5V28 missile missed the drone and exploded some 15m above the Tu-154M. The aircraft sustained serious damage, resulting in a decompression of the passenger cabin.”

Ministerie van Defensie, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

This, and subsequent shoot downs – most notably Malaysia Airlines flight 17 en route from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur on 17 July 2014, while flying over eastern Ukraine, and Ukraine International Airlines flight 752 seven minutes after its departure for Kiev from Tehran’s Imam Khomeini International Airport on 8 January 2020 — are unquestionably classifiable as security incidents. The prevention of such acts depends upon effective risk analysis achieved by a thorough understanding of conflict zones and the weaponry deployed within them and, in tandem with that, decision-making responsibility, often resting in the hands of an individual employee within an airline’s security department to demand alternative routes be flown, delay the departure of a flight and/or even cancel flights completely…regardless of the commercial pressures that may be present.

In terms of what might be described as the more traditional attacks against aviation perpetrated by passengers, crew and/or those who had access to baggage, cargo or the aircraft whilst on the ground, it was only just over three months after 9/11, on 21 December, that Richard Reid attempted to destroy an American Airlines flight en route from Paris to Miami. Commonly referred to as the ‘shoe bomber’, Reid was identified as a potential threat to the flight by one of ICTS’ security screeners when he checked in for the flight – an excellent example of the value of passenger profiling. They did not find the bomb itself, rather they identified Reid as somebody worthy of enhanced screening that there was insufficient time to perform before the flight’s departure. Consequently, Reid was booked into a hotel for the night only to return the next day and be granted permission to board. IMAGE: Richard Reid Shoe Bomber.jpg His attempts to ignite the fuse in his shoe failed and he was overpowered by passengers and cabin crew. The industry responded by asking passengers to remove footwear that they had previously been permitted to wear as they passed through archway metal detectors.

On 7 May 2002, a China Northern Airlines flight crashed on a domestic flight en route from Beijing to Dalian’s Zhoushuizi airport. All 112 on board lost their lives after a gasoline-fueled fire was deliberately started on board by Zhang Pilin. IMAGE: Zhang Pilin.jpg There are a variety of explanations for Pilin’s action, some political, others simply putting it down to his trying to provide for his family; he had taken out seven life insurance policies on the day of the disaster – some in the morning in Dalian, prior to flying to Beijing, and the rest prior to his return flight. With the incident taking place in China and there being limited media coverage of the incident, it had next to no impact on global aviation security measures. In any case, most regarded it as a safety incident rather than a security one.

Marauding Firearm Attacks

Whilst there have been no fatalities as a result of hijackings since 9/11, the same cannot be said for marauding firearms attacks, and bombings, at airports. On 4 July 2002, celebrations for America’s Independence Day were overshadowed by a terrorist attack at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) in which Hesham Mohamed Hadayet opened fire at the El Al Israel Airlines check-in.

Hadayet was reportedly infuriated by the proliferation of American flags on buildings near his home in the aftermath of 9/11. Armed with a .45 Glock pistol, a 9mm handgun and a 6in hunting knife, he entered the terminal and shot the check-in agent, Vicky Hen, in the chest. He then shot Yaakov Aminov, a bystander who had brought a friend to the airport, before he was overpowered by two El Al security guards and passengers and eventually shot and killed by El Al’s Haim Sapir, demonstrating the value of having armed guards on hand.

It was not the only shooting at a US airport since 9/11. On 1 November 2013, also at LAX, Paul Anthony Ciancia opened fire with a Smith & Wesson M&P-15 rifle, killed Gerardo I. Hernandez, a TSA behaviour detection officer, and injured five others before being arrested. And, on 6 January 2017, Esteban Santiago-Ruiz opened fire in the baggage reclaim area at Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport, killing five and injuring six others. Whilst Ciancia had some warped political agenda and detested the TSA, Santiago-Ruiz was later determined to be suffering from schizophrenia.

Mental Health

No airline or airport can claim to be immune from the actions of those with mental ill health which, in extreme circumstances, can result in actions that are a far cry from the actions of terrorists but with potentially equally catastrophic results. There have been at least two incidents in which passengers on domestic flights have attempted to gain access to the cockpits of flights of which they were travelling as passengers with suicidal intent.

It was a paranoid schizophrenic passenger, David Mark Robinson, who attempted to bring down a Qantas domestic flight en route from Melbourne to Launceston on 29 May 2003. Armed with wooden stakes — designed to circumvent identification by the archway metal detector — which were concealed in his jacket pockets, Robinson arose from his seat when the seatbelt sign was turned off and commenced his frenzied attack on flight purser Greg Khan in an attempt to gain access to the flight deck. He allegedly wished to crash the aircraft into the Walls of Jerusalem National Park in Tasmania. Why? According to the Australian Federal Police, Robinson told them that he had travelled around Australia looking for a woman wearing crimson and scarlet as that would be an indication of where the devil lived. He saw a woman wearing crimson and scarlet whilst in Tasmania and, believing he was expected to rid the world of the devil, so determined the intended crash site for his suicidal mission. He was found not guilty due to mental impairment.

Just over a year later, it was a domestic flight on the other side of the world — Norway — which was to become the target of a suicidal hijacker. On 29 September 2004, armed with an axe, Brahim Bouteraa boarded his flight with ease in Narvik; there was no screening for domestic flights. Benefiting from the absence of both cabin crew and a cockpit door on the Dornier-228, Bouteraa accessed the flight deck and attacked the crew intent on causing the aircraft to crash as it descended towards Bodø. Bouteraa had been denied asylum by Norway and was to be deported back to Algeria; he was…but only after serving ten of his fifteen-year sentence for hijacking.

Russia’s 9/11 & The Move Towards Liquid Explosives

It wasn’t on 11th September and there were nowhere near as many casualties, nor was there any destruction caused to city centres. That said, the ingenuity of terrorists and their willingness to kill innocent people was demonstrated by the simultaneous bombing of two Tupolev aircraft on 24 August 2004.

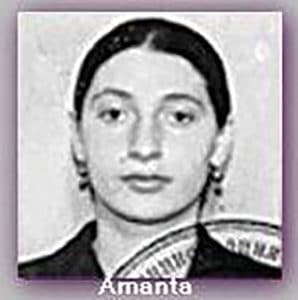

Amanata Nagayeva and Satsita Dzhebirkhanova, were the alleged bombers, both Chechen women who had paid bribes to avoid ID checks at Moscow’s Domodedovo airport prior to their departure on separate flights. Residents of Grozny, Nagayeva was single and Dzhebirkhanova divorced, but they both qualified to be described as ‘Chechen Black Widows’. Nagayeva’s brother had disappeared in Chechnya having been allegedly abducted by Russian forces, whilst Dzhebirkhanova’s brother — an Islamic court judge — had been killed back in 1998. They had the motivation and the conviction, whilst their hexogen-based explosive charges had the power to perforate the fuselage of their respective aircraft.

43 lives were lost on Volga-AviaExpress flight 1353 as it flew towards Volgograd and exploded over Tula Oblast, whilst 46 people perished aboard Siberia Airlines Flight 1047 en route to Sochi.

Whilst 9/11 and even the Lockerbie bombing continue to command newspaper headlines, the Russian bombings have been forgotten beyond Russian shores. The attraction of targeting multiple airliners on the same day had not diminished within terrorist circles. It was in August 2006 that the news broke that the security services had identified a plot to destroy multiple aircraft operating from the United Kingdom to the United States and Canada using ‘liquid explosives’.

The terrorists were to board flights with the component parts of the IEDs, only to combine them on board in the secrecy of the aircraft toilets, the location, we believe, Nagayeva and Dzhebirkhanova had detonated their devices in two years earlier. The basis of the explosive of choice was hydrogen peroxide, readily purchased across the counter in the UK. Prior to boarding, the substance was to be mixed with a drink powder, Tang, so that it would look like a typical soft drink and injected into 500ml plastic bottles so that the seals would appear intact. The remainder of the device was to be concealed inside AA batteries and disposable cameras with in-built flash units.

Such was the sophistication and ingenuity of the supposed explosive devices, traditional screening processes were deemed incapable of detecting them. This resulted, initially, in the banning of all carry-on baggage and, subsequently, to the more workable restriction on the carriage of liquids, aerosols and gels. Whilst completely understandable at the time of the plot, such restrictions should no longer be part of our security regime, regardless as to whether or not more advanced technologies can detect substances of concern. Far too many screeners feel that they have achieved something by identifying an innocuous tube of toothpaste or bottle of perfume; this simply distracts them from focusing on the real threat. Meanwhile the limitations in overall quantities of liquids being taken through checkpoints are only limitations on what any one individual can carry; it is still possible for teams of terrorists to take large quantities of liquids through checkpoints. I accept it may have some deterrent value but, as we were to witness on Christmas Day 2009, and in other subsequent attacks, there are different ways of infiltrating explosive charges onto aircraft. Prohibited and restricted items lists distract us from focusing on intent.

Liquid explosives could be used in different ways — and were, including on 30 June 2007 when two men drove a Jeep into the terminal building at Glasgow Airport laden with propane.

More significantly, on 7 March 2008, Guzalinur Turdi attempted to set fire to a China Southern Airlines flight bound for Beijing from Urumqi in Xinjiang Province. Turdi smuggled gasoline on board — as Pilin had done six years earlier — and planned to cause a fire in the aircraft’s toilets. However, an observant crew, concerned about the odour of the 19-year-old, alerted the sky marshals who overpowered her before the gasoline could be ignited.

Better known, because it involved a flight from Europe to the United States, is the case of Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab (a.k.a. the ‘underpants bomber’) who, on Christmas Day 2009 managed to board a Northwest Airlines flight to Detroit with an explosive device stitched into his underwear. The first security agent who interviewed Abdulmutallab in Amsterdam did express his concerns about the passenger, but Abdulmutallab was not screened in any greater detail and managed to board the flight. Luck was on the side of his fellow passengers and crew; Abdulmutallab attempted to detonate the device, but the explosion did nothing more than harm his nether regions.

International aviation security measures were, once again, set to change. Cue the introduction of the body scanner! Systems based on transmission X-ray, backscatter X-ray and millimetre wave imaging were all developed. The most effective detection systems were not to be deployed as unfounded concerns about irradiating passengers resulted in the adoption of millimetre wave as the preferred solution, despite the fact that customs agencies around the world were already using transmission X-ray systems at airports to detect internal carries of illicit substances. And the civil libertarians, concerned about the images of passengers’ body forms, managed to persuade the industry to utilise avatars (or stick figures) rather than actual imagery of people.

The Printer Bombs

There can be no better modern-day case study to support the implementation of profiling than the attempted bombing of two airliners on 29 October 2010…with not a single person in sight to perform behavioural analysis on!

The two bombs were sent as courier shipments from Yemen to the United States. We were fortuitous that Saudi Arabian intelligence services identified the plot and notified their international counterparts resulting in the two suspect packages being set aside for enhanced screening at UK’s East Midlands airport and in Dubai. The British authorities reportedly failed to detect the explosive charge as they had relied on technology to screen the package — technology which did not alarm. The package was cleared for onward travel. In Dubai, however, the screening supervisor was not accepting the lack of any alarm as justification to allow the package to continue its journey. First, there was the intelligence they had received, but then there was the fact that people do not normally ship computer printers from Yemen to the United States. Additionally, when checking the address the consignment was being sent to, he found that it was associated with the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Jewish community of Chicago — even for an Emirati screener, unversed in the nuances of Jewish communal life, he found that somewhat strange given that the package had originated in Sana’a. His team located the IED and alerted their British colleagues who then found the charge similarly concealed in the printer toner cartridge.

The industry responded with a call for increased inspections of cargo consignments. Rather bizarre considering that technology had failed. When one considers that, in 2019, airlines reported carrying 4.3 billion bags and more than 61 million metric tonnes of cargo per year, if we couldn’t find an IED in a consignment we were told was likely to contain a bomb, how on earth can we expect to detect such a device with routine screening?

The hijacking of Tianjin Airlines flight 7554 on 29 June 2012 further demonstrated the limitations of technology and the need for us to think outside the box. Six hijackers boarded the flight to Urumqi in Hotan managing to infiltrate their weapons and explosives through the checkpoint within the aluminium crutches of one of the group feigning to be disabled. CCTV footage shows the crutches being passed over the X-ray machine at the checkpoint. The hijackers were overpowered by passengers and crew.

Aircrew Mental Health

Over the last decade, there has been increasing concern about the risk of acts of aircraft-assisted suicide. On 29 November 2013, Mozambique Airline flight 470 crashed in Namibia whilst en route from Maputo to Luanda resulting in the loss of 27 passengers and six crew.

Shortly after the aircraft passed through Botswanan airspace, the first officer left the flight deck to use the toilets. Captain Herminio dos Santos Fernandes, left alone on the flight deck, despite that not being in accordance with Mozambique Airlines’ Flight Operations Manual, then locked the door and initiated a controlled high-speed descent.

The Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) did record the sound of knocking on the flight deck door but there was no response from the flight deck. Yet the CVR also revealed that the captain was conscious and in control. The enhanced flight deck door, which had become standard post 9/11 to prevent the ‘bad guys’ gaining entry to the cockpit, had now become a barrier to the ‘good guys’ being able to overpower the ‘bad guy’ at the controls.

The aircraft eventually crashed in Namibia’s Bwabwata National Park; the wreckage was only found a day later.

The subsequent investigation revealed that the captain had been going through a number of highly stressful challenges at the time of the crash: his son had been killed in a car crash one year and a week beforehand, and seemingly in an act of suicide; he had, for ten years, been going through a divorce which was still not resolved; and, his youngest daughter was in hospital having gone through heart surgery. But the incident prompted no response from the industry. After all, it happened in Africa.

The speed at which the industry reacted to the loss of Germanwings Flight 9525 on 24 March 2015 was far more rapid – arguably too rapid with some carriers implementing new measures overnight without providing their crews with the necessary training.

Once again, a passenger jet was intentionally crashed by one of its pilots and once again the cockpit door had been locked – this time after the captain left the flight deck to use the toilets leaving the first officer, Andreas Lubitz, alone — preventing the remaining crew from overpowering the suicidal individual who had orchestrated a controlled descent into the Alps.

Lubitz had been receiving treatment for depression for many years and had reportedly had suicidal tendencies. Investigators found a medical note in his home signing him off sick, but Lubitz had thrown this away and the doctors treating him were under no compulsion to report their concerns to his employers. Indeed, they were prohibited from doing so due to patient/doctor confidentiality protocols in place in Germany.

There have been a number of other acts of pilot suicide. Most have involved pilots of light aircraft using their vehicles to terminate only their own lives and not commit acts of mass murder. One possible exception to that I have not dwelt upon in this article; seven years on, we still do not really know what happened to Malaysia Airlines flight 370 on 8 March 2014. All we do know is that aircraft-assisted suicide is considered by many to be the cause of the loss of that aircraft, whilst en route from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing, and its 239 passengers and crew.

Insiders

Ask any group of new hires to put themselves into the shoes of a terrorist and design an attack against their own facility and you’ll find that many of the plots will involve the use of industry insiders – aircrew, cleaners, caterers and baggage handlers. The last few years have, however, demonstrated that the insider threat is a very real challenge.

Given that so much effort has been put into promoting known or trusted traveller programmes, where the amount of information we have on people is miniscule in comparison to that which we have on the staff we have vetted to work within our operations, I think it is reasonable to question whether there can ever be such a thing as a trusted traveller.

Metrojet flight 9268 was blown out of the skies on 31 October 2015 killing all 224 souls on board the aircraft which had departed Sharm el-Sheikh for Saint Petersburg. It remains unclear as to how the improvised explosive device was infiltrated on board, but Russian sources believe that it was placed between two suitcases by a baggage handler who was operating on behalf of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant’s (ISIL) Sinai Branch. Egyptian authorities rejected this claim.

Africa was to be the scene for the next bombing attempt, this time of Daallo Airlines flight 159 bound from Mogadishu to Djibouti on 2 February 2016. The IED was concealed in a laptop computer which was handed to the bomber, Abdullahi Abdisalam Borleh, after he had already been through the airport security screening process. Borleh detonated the device as the aircraft climbed through 11,000 feet and the subsequent blast blew a hole in the aircraft large enough for Borleh himself to be sucked out of the aircraft. The aircraft was not flying high enough for the bomb to achieve its intended level of destruction and the crew managed to safely land the aircraft back in Mogadishu.

Somalia set about charging those al-Shabaab operatives behind the attack, some of whom were airport workers; at least one worked in an airport security managerial role — Abdiwali Mahmud Maow was given a life sentence.

It was not long before the threat of IEDs concealed in laptop computers resulted in additional restrictions on passengers carrying such devices on certain routes associated with the region.

Airport Attacks

Testament to the perceived effectiveness of the security screening processes in place, inflight and airside attacks have been a rarity. But aviation interests have remained an attractive target.

On 22 March 2016 three terrorists took a taxi to Brussels’ Zaventem Airport, carrying with them three large suitcases laded with explosives. Minutes later 16 people were to die when two of the suicidal terrorists detonated their devices. It was all too simple. Few airports in the world have screening prior to entry to the passenger terminal. Perhaps, therefore, it was not surprising that many advocated for such screening measures to be implemented…just as they were already doing in Istanbul! And so, Belgium began screening people who wished to enter the terminal.

Yet three months later, on 28 June 2016, at Istanbul’s Atatürk Airport an even more deadly attack took place. 45 people were killed as the marauding firearms attackers opened fire at the checkpoints at the entrance to Terminal 2. When security forces returned fire, two of the terrorists detonated their explosive vests; one of the terrorists made it into the terminal and was eventually neutralised by the security forces.

Whilst many readers may recall these two incidents, there were also two other significant airport attacks that preceded them. On 24 January 2011, the arrivals hall of Moscow’s Domodedovo airport was the target of a suicide attack orchestrated by the Islamist Chechen leader, Doku Umarov, and perpetrated by 20-year-old Magomed Yevloyev. 37 people were to die and almost 200 were injured.

A year later, on 18 July 2012, Mohamad Hassan El-Husseini was recorded on CCTV wandering around the arrivals hall at Bulgaria’s Burgas airport, awaiting the arrival of a flight from Tel Aviv. As they exited customs, El-Husseini followed the Israeli passengers to the tour bus waiting to transfer them to their hotels. He loaded his backpack into the bus and an explosion took place which killed 6 people, including the Bulgarian bus driver, and injured almost 30 others. Some questioned whether El-Husseini was actually a suicide bomber and mooted that he may have believed he was simply infiltrating an IED onto the bus, unaware that he was to be sacrificed in the mission.

Only last year, the Bulgarian courts sentenced, in absentia, Meliad Farah, a Lebanese-Australian, and Hassan El Hajj Hassan, a Lebanese-Canadian, to life imprisonment for the Hezbollah-sponsored attack.

Aircraft inflight remains the ultimate target for terrorists and it was an Etihad flight operating from Sydney, Australia to Abu Dhabi that was supposed to be the casualty on 15 July 2017. The bomb was concealed within a meat grinder to make identification under X-ray examination nigh on impossible. And the grinder itself was to be taken on board unwittingly by Amer Khayat, the younger brother of the bomb makers Khaled and Mahmoud Khayat. It is thought that they were prepared to sacrifice their younger brother due to their distaste for his lifestyle, which included his being openly homosexual.

Amer had been told that the meat grinder was simply one of the many gifts that the brothers were sending with him to family in the Middle East. But he was carrying too much hand-luggage — three different items, one containing the bomb — and the Etihad ground handling agent asked that he check-in some of them as hold baggage. Amer, and Khaled, who had accompanied him to the check-in counter, returned to the car, where Mahmoud was waiting, to repack the bags. Khaled and Mahmoud decided that there was too much focus on Amer’s baggage by then, so they removed the meat grinder and sent Amer off to Abu Dhabi without the bomb; they took the device home, deactivated it and set about replanning their attack. Thanks to the Australian intelligence services efforts, the men were arrested on 29 July before they were able to initiate an attack against any other airliner or complete their other intended mission of a poisonous gas attack in a crowded downtown area.

The Etihad plot demonstrates the continued use of new items to conceal explosive devices and the Australian bombers’ willingness to explore the potential for chemical weapons attacks. The aviation industry is behind the curve when it comes to countermeasures in place to guard against a chemical or biological weapons attack.

More Recently

With fewer passengers flying nowadays as a result of COVID-19, a terrorist attack against aviation has probably been less likely to occur. The paperwork checks people have to go through in order to board aircraft certainly act as a deterrent. But as the vaccination programme expands and travellers return to the skies so too must we be ready to respond to the actions of those who have used the period of isolation to become further radicalised or more estranged from society.

Incidents are still taking place. Drone attacks launched by Houthis against Saudi Arabian airports have been all too frequent an occurrence, stowaways are still clambering into wheel wells of aircraft to fly to pastures greener, protests for a multitude of arguably worthy causes are disrupting airport operations, cyberattacks for financial gain have been increasing at alarming rate and aircraft have been targeted at remote landing strips in incidents rarely reported internationally.

Xuddur Airport in Somalia was, on 7 October 2017, the scene of one such incident in which a Penial Air Cessna Grand Caravan was attacked as it was taxiing for departure. Two armed men started firing at the aircraft as the pilot tried to take-off; he had to abort but, in doing so, lost control of the aircraft and it crashed into a building. All passengers and crew survived the incident but the aircraft itself was seriously damaged.

I conclude with three events from this year.

On 23 May, Ryanair flight 4978 was operating from Athens to Vilnius when, whilst in Belarusian airspace, it was ordered to divert to Minsk. The authorities in Belarus claimed that the aircraft was the target of a bomb threat. The crew complied with the request even though Vilnius was actually closer to their actual location than Minsk. Once on the ground, one of the passengers, Roman Protasevich, was arrested. Protasevich is a journalist who is vociferous in his opposition to the government of Belarus, to the extent that he had claimed asylum in Poland in 2020. When he realized the aircraft was diverting to Minsk he told fellow passengers that he feared he would face the death penalty. From an aviation security perspective, the actions of Belarus were widely condemned, including by Ryanair’s CEO, Michael O’Leary, who described it as a “state-sponsored hijacking”.

I earlier referred to aircrew mental health, but in my introduction I highlighted the general threat to aviation posed by those who are experiencing mental health challenges. This was exemplified on 7 July when 18-year-old Jaden Lake-Kameroff, a passenger on a Ryan Air flight en route from Bethel to Aniak in Alaska, tried to seize the controls of the Cessna Caravan and force it into a nosedive. The pilot managed to regain control of the aircraft as the other four passengers held the assailant until they had landed safely in Aniak. Lake-Kameroff admitted he was trying to kill himself in the act.

It seems apposite to conclude this review of the past twenty years of aviation security, which started with the attacks of 11 September 2001, with the horrific act that took place at Kabul Airport on 26 August 2021. It was a failure of aviation security that resulted in a western presence in Afghanistan and the Taliban being ousted from power. Twenty years on, the ideology that resulted in the loss of 2,977 lives in the United States claimed at least 182 more lives in Afghanistan when a suicide bomber detonated their vest at the gates to the airport.

The withdrawal from Afghanistan may be deemed to be politically expedient, but what happened in Kabul only a month ago demonstrates that we have far from won the war and we must all remain on our guard.

Philip Baum is Managing Director, Green Light Ltd., and Visiting Professor, Aviation Security at Coventry University. He can be contacted at editor@avsec.com