There is no doubt that new access/surveillance technology and advanced security monitoring solutions can improve security everywhere from airports and bus stations to mass transit, trucking and trains. At the same time, it is possible to improve security at any location without increasing costs. Here’s how to do it.

Adapt Your Security SOPs to Reality

All major transportation facilities have some sort of security infrastructures in place, along with Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) to direct staff on how to manage and maintain these facilities.

In theory, all the staff have to do is to follow these SOPs to keep their facilities secure. In practice, however, this often doesn’t happen. One major reason: “A lot of the time when you find that staff [are] not following correct SOPs, [it] may be an indication that the SOPs are wrong,” said Shannon Wandmaker, director of Cain Wandmaker Aviation Security Consulting (cainwandmaker.com). “Obviously it can be an indication of other things as well — poor training, low staff morale, challenging work environment — but along with looking at those factors, security managers should remember to review the SOPs themselves, and to discuss the SOPs with the staff who are implementing them.”

Often the fixes being used by staff achieve the intent of the SOPs, even if they don’t follow them. This disconnect can occur because SOPs are often developed using a top-down approach, Wandmaker noted. “The national requirements say we need to do X, so our security manual says to do X, so the SOPs says, ‘this is how to do X.’ However, if the front-line staff are doing Y, and that achieves the same security outcome and meets the national requirements, then let them continue doing Y, and change the SOPs.”

Working with security ‘workarounds’ that work achieves two goals. First, “it means the company doesn’t have to waste time and money re-training people to do something a different way for no reason,” said Wandmaker. Second, adopting staff-developed SOPs “also gives front-line staff an opportunity to be heard, and feel that they have contributed to the outcome, and that has the side benefit of improving staff morale and engagement. People are more likely to follow an SOP that they helped write, than follow one that was imposed on them.”

Turn Down the Noise

Remember the old fable of The Boy Who Called Wolf? In this tale, a boy shepherd enjoys riling up his neighbors by calling ‘Wolf!’ when there isn’t one. After a while, his fed-up neighbors stopped heeding his calls, even when an actual wolf attacked the flock and ate them — and in some versions of the story, the shepherd as well.

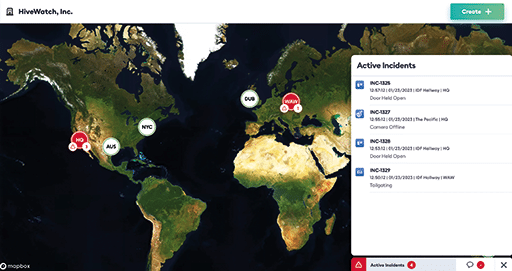

This same scenario plays out today in transportation security. “Most transportation security hubs — such as airports, mass transit and ports — have global security operations centers (GSOCs) that provide security oversight for these locations,” explained Rebecca Sherouse, director of account management and security advisory at HiveWatch (hivewatch.com, a cloud-based SaaS platform built for physical security teams). “But almost all of these are plagued with “noise” — that is, false incoming alarms that detract from actual events that are occurring. As a result, GSOC operators are overwhelmed and become desensitized to incoming alerts, which can result in missed events and/or emergencies across the transportation sector.”

The solution to this problem? Reduce the number of false alarms due to proper equipment maintenance, a resetting of triggering thresholds so that alarms aren’t being set off by animals and natural phenomena, and any other adjustments that make sense. If security staff know that they can generally trust the alarm messages that they are receiving, they will be far more likely to respond to them.

A further way to cut down the noise is to modify GSOC operations to provide security staff with an integrated view of what’s going on across all of their facilities, so that they can make rational and timely security responses without drowning in data.

Here’s the problem: “There are a lot of devices deployed across the transportation sector, from access control points with varying levels of access, to video surveillance across the entire facility/geographic area, to video management systems, to fire and intrusion detection points, and much more,” Sherouse said. Without some sort of integration platform in place to organize and prioritize this information. “The wealth of data coming out of these various devices and systems can quickly overwhelm physical security operators, who often have to navigate to multiple locations within a GSOC to correlate data, video and other information when conducting an investigation or responding to an alert,” she told TSI. “The biggest lapse for this industry is the inability to correlate all of the incoming data into a cohesive view for an operator designed to streamline response and provide the most accurate and up-to-date information that’s needed to facilitate decision-making.”

Cutting down on the noise while making security jobs more decision-oriented and less a case of passively watching monitors can also lead to more consistent GSOC staffing, expertise and performance. This is because “GSOC operators traditionally have a high rate of turnover because of the largely repetitive nature of the job,” said Sherouse. “Incoming alarms can exacerbate this by becoming a hindrance to response in many situations. This can lead to lower morale and high turnover, which can in turn lead to insufficient training to deal with emergencies as they happen. That’s the last thing that an organization wants when an incident arises — especially in such a critical sector.”

Replace Humans at Access Points with Machines

It is possible to buy new technology and improve security without increasing costs, once the money being saved by the technology’s operations is factored into the equation.

A case in point: “One of the major lapses that exists in transportation security is management of exit lanes and employee access lanes,” said Frederick Reitz, managing director of the aviation security firm SAFEsky. “Most airports have an exit area that must be manned by a security guard or TSA agent (in the U.S.). The standard cost for putting a security guard or TSA agent at an exit lane for 12 months averages approximately $250,000.”

Now, it would cost about $500,000 to replace that one guard with four exit lanes controlled by one automated terminal, he said. But do the math: “The investment of the automated secure exit lanes would pay for itself in two years,” said Reitz. After that, the money saved by not having a human guard would be a bonus.

That’s not all. “Automated lanes are an effective way to prevent access to the secured area,” he said. “They are always watching, and do not open if a person tries to enter from the wrong direction.” In contrast, a human guard requires breaks for meals and restroom use, and their attention can be diverted by passengers asking questions or a staged incident meant to distract them.

Training and Morale Matters

One reason why it is possible to improve security without raising costs is because humans operate security systems — and the training of these humans can be improved by simply executing existing training and morale support programs better. “Regardless of the quality of equipment in place, the quality of the people using that equipment will always be the determining factor on how well the equipment works,” observed Wandmaker. “A one million dollar piece of equipment, operated by someone who has had $1 of training, is worth $1.”

As for the fond hope that advanced technology can compensate for poor operator training and, by extension, poor management by those in charge of such operators? Don’t kid yourself: “No one puts a pilot with half an hour of training in charge of a brand new Airbus A350, no matter how technologically advanced the autopilot is,” Wandmaker said. “Similarly, if you want to get the best performance out of your security equipment, then you need to give the people using that equipment the best possible training and ongoing support.”

It’s ongoing support that organizations will often forget, he warned. Successful staff training does not mean delivering a course once and then never again. Instead, “it’s about initial training, refresher training, support and mentoring, creating career pathways (that include appropriate additional training for supervisors, managers, specializations), and a host of other things,” said Wandmaker. Ongoing support not only ensures staff skills don’t fade over time due to training neglect, but “that they feel like a valued part of the organization, and that their role is not just ‘a job’, but could be an actual career path for them if they wanted it.”

In saying this, Shannon Wandmaker acknowledged that every organization will have limitations in what they can deliver in terms of ongoing support for their staff, based on their size and revenue. “A large multinational manned guarding company will have far more scope to deliver ongoing training, mentoring and career pathways than a small transport and logistics company with three security officers on its books,” he said. “But it’s about doing what you can within each organization’s own reasonable financial and other limits.”

Frederick Reitz is another big believer in ongoing training and support. But he thinks its reach has to be extended to everyone in the organization whose job has an impact on facility security, not just the people manning the desks at the GSOC.

“To prevent lapses in security, it is important that airports and airlines conduct annual security training, through online training modules or in-person classes, to remind staff of the security procedures,” he said. After all, “airline and airport staff are a part of the security process, they are the eyes and ears of the security system. They need to be observant and watch for suspicious activity and unusual events at the airport, on the plane.” According to Reitz, training should include a reminder of facility security procedures, and access control regulations for staff on duty and off duty. Training should include current threat information and a reminder for staff to be aware of their surroundings.

Preventing a Return to Bad Habits

All of the ideas noted above can help improve facility security without boosting costs. But all of the effort required to implement them won’t be worthwhile if staff are allowed to slip back into bad habits six months down the road. This is why security managers have to be vigilant in maintaining the improvements they have made to date, and watchful for new ideas to implement going forward. “In an industry that is constantly addressing new and emerging threats — and taking action to determine the best way to address them — continuously updating response protocols and incorporating them into training of GSOC operators remains critical,” said Sherouse.

“Quality assurance and oversight: It doesn’t matter whether it’s a private organization or a State regulator, around the world one of the biggest areas where organizations let themselves down is quality assurance and oversight,” Wandmaker said. “Organizations put policies, rules, SOPs, guidance material in place, train their staff on it, and then fail to conduct effective QA. And then they wonder why their security outcomes are poor. Effective QA pays for itself, because in addition to identifying poor security outcomes and ensuring they’re corrected, it also allows organizations to review security settings on a regular basis to identify inefficiencies in systems. Good security has a layered approach, but great security ensures only the effective layers are kept.”

Taking the time to maintain security procedures, training, and staff morale is central to keeping bad habits at bay. “Lapses in security occur when we are in a hurry,” said Reitz.

Two examples prove his point. In the first, “as an airline security manager, I was called to the security checkpoint when a flight attendant, rushing for a flight after a layover, forgot she had a knife in her lunch bag,” Reitz said. “Initially, TSA wanted the flight attendant charged with introducing a prohibited item into the secure area. Fortunately, after investigating the circumstances, she was allowed to continue her flight — without her lunch bag.”

In the second instance, “an airport agent wanted to go to the gate and say goodbye to a friend, and used the employee entrance to the secure area,” he said. “This also could have resulted in a one-year suspension of the employee’s airport ID. [But] reasonable heads prevailed and a five-day suspension was given. Security training needs to include examples of these events to remind employees that procedures are in place for a reason, and that rushing often leads us to forgetting the importance of a procedure.”

Three Final Fixes

To conclude this article, the three security experts we interviewed were asked for three final security fixes.

Rebecca Sherouse recommended using “technology to identify and reduce false alarms that take valuable time away from security operators to respond to real emergency situations.”

Shannon Wandmaker said that transportation facilities need to review their security risk contexts statement (or create one, if they don’t already have one), and re-conduct their risk assessments to keep them relevant and useful. “What has changed? Are the threats the same as they were one year ago? Five years ago?” he said. “Are we defending against threats that don’t exist anymore, but not defending against emerging threats? For example, an organization may have previously been concerned about the impact of civil unrest in their country and how that could impact on their supply chains. However, the political situation has stabilized, but the company hasn’t removed the additional security measures. At the same time, they have missed the emergency of cyber security threats, and are grossly under-defended against this much more possible attack.”

Frederick Reitz offered a different view. “The single least expensive way to improve security is to keep staff involved,” he said. To make this happen, “security managers can provide newsletters, bulletins and briefings. Gathering the staff occasionally to have a security briefing not only keeps the importance of security in front of the staff but opens the doors for communication and gives them the opportunity to provide input.”

The bottom line: As this story shows, it is possible to improve security without increasing costs — right here and right now.