Threat Image Projection or TIP was first incorporated as a standard feature in X-ray Baggage Scanners in the late ‘90’s. Libraries of images used for operator training, as well as maintaining operator alertness, is its goal. But is the program working? Is it enough? Is it even needed? Here we have two viewpoints — a point/counterpoint, if you will. First up, Tom Campbell, who has developed TIP training images for 40 years makes a strong case for their use, followed by security training expert Guilia di Cato’s opposing view, starting on page 20.

Overseas Territories Aviation Circular (OTAC) 178-3 issued by ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organisation) requires under Sec 2.1 that:

(a) If the TIP library consists of Combined Threat Images (CTI), it shall comply with the following:

(1) It shall contain a minimum of 6,000 virtual images, of which at least 250 threat articles shall be captured in different orientations: and

(2) No fewer than 100 virtual images shall be replaced with new images each year, the oldest images being replaced first: and

(b) If the TIP library consists of Fictitious Threat Images (FTI), it shall comply with the following:

(1) It shall contain a minimum of 6,000 virtual images, of which at least 250 threat articles shall be captured in different orientations: and

(3) No fewer than 100 virtual images shall be replaced with new images each year, the oldest images being replaced first.

Paragraph 3.1 of the ICAO document states:

The intention of the requirements is that TIP systems are kept up to date, with images that reflect emerging threats, and are effectively used as part of a management and screener certification process.

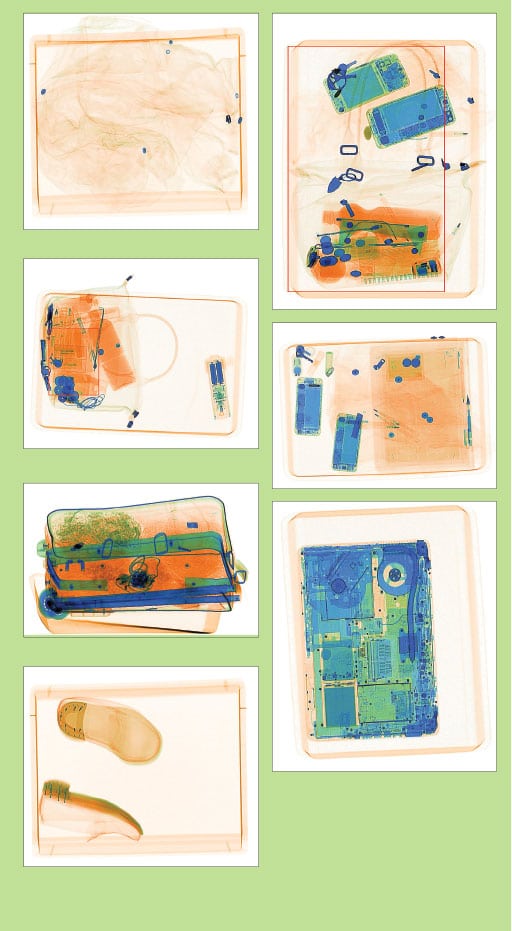

Threat Image Projection or TIP was first incorporated as a standard feature in X-ray Baggage Scanners in the late ‘90’s. The first TIP libraries consisted of Combined Threat Images or CTIs where prohibited articles were placed bags with contents and the resultant images recorded and stored in an indexed library on the hard drives of the operating systems. These images were then inserted into the bag stream as viewed by the operator.

Subsequent developments in software and computing power enabled the production of Fictitious Threat Images or FTIs, where the threat object itself is scanned and catalogued, then projected into a live bag.

In two-dimensional X-ray images this is no mean feat as the projected object, as a collection of pixels must:

1. fall within the boundary of the bag, another collection of pixels: and

2. track with the bag image as it moves across the operator’s screen.

Dual view systems provide an even more complex challenge for FTI images as they must conform across both views.

With Computerised Tomography (CT) systems this becomes even more complicated as the TIP insertion algorithm must find a collection of voxels (volume pixels) within the bag image, that represents a low-density area (organic clothing or an ‘empty space’) which matches the threat volume and insert the threat object, another collection of voxels within that void while ensuring that the resultant threat image is not intersected by the other bag contents.

Further complication in production of CTIs was introduced with the adoption of baggage tray systems. Many trays are fitted with Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags, not to mention the fact that loaders will position the tray askew on the belt so that a tray that is perfectly aligned is immediately flagged by the screener, as a TIP inserted object

While the OTAC requirements are perfectly clear, many countries do not implement them, treating ICAO documents relating to aviation security as purely advisory, therefore, Countries may or may not require TIP programs to be part of the tender requirements issued to manufacturers of baggage and freight screening systems.

How are TIP libraries Produced?

At present there two general agencies involved. The screening system manufacturers and government bodies such as CAA in UK and FAA/TSA in the U.S. who use government contractors to produce the libraries. In UK and the US, there is strict oversight of the images produced and adherence to the ICAO recommendations, though unfortunately in other states, the recommendations are more honored in the breach than the observance.

Manufacturer’s libraries are comprehensive, though sometimes the images tend to show the systems in a good light rather than reflecting the more difficult threat items or items that the EDS algorithm cannot detect.

Internationally, peer review of TIP images is rarely done, and most states simply accept the libraries that the manufacturers produce, although in UK and ECAC areas at least, there are established bodies, in the form of the Department for Transport (DfT) who oversee the TIP project through the Aviation Security Branch of the Civil Aviation Authority, and they manage the TIP libraries; vetting each image for relevance and difficulty and applying the recommendations of the ICAO document. That being said, some government bodies have a tendency to politicize matters of National Security and so TIP becomes a yardstick by which to measure performance which can be tweaked to produce favourable results by inclusion of indicator marking in the image. However, the metrics of TIP while of some interest to statisticians, are of secondary value to the teaching and maintenance of pattern recognition skills that are provided by the images.

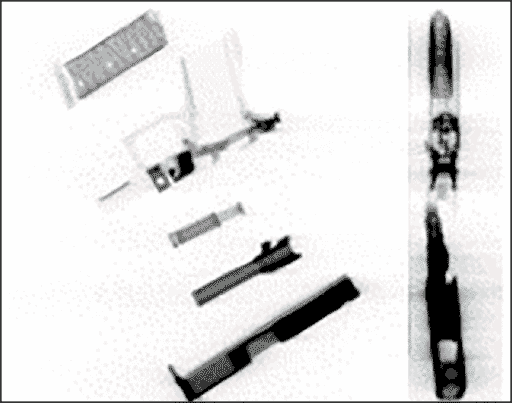

TIP libraries are time consuming to produce and companies involved in this must work within their country’s legislative framework. In the U.S. for instance, legislation regarding firearms varies from state to state and it is more cost effective to transport an X-ray machine that is manufactured in one state, say, Massachusetts, with tight firearm legislation, to an adjacent state, New Hampshire or Maine for instance, where firearm legislation is less rigorous; in order to carry out the imaging process, than to jump through the licensing hoops of the originating state’s regulations. For this reason, many libraries contain few actual firearms but many pellet and paintball guns. These are not realistic firearm images though that is not to say that they should not be excluded from the library as they are prohibited from carriage on board an aircraft. Actual weapons can be broken down to their individual parts providing a much more realistic image as shown below.

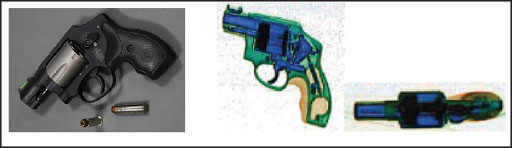

In the firearms industry there is constant development and manufacturers are quick to adopt new materials such as in this Smith and Wesson with a stainless-steel barrel, scandium alloy frame and titanium cylinder shown below.

In dual view this does not look much different to the standard ‘revolver’ image, but in contrast this is a USFA ZIP .22LR. Mostly plastic but with metal components.

Other new types may not look like firearms such as the Ideal Conceal folding backup pistol (image top of next column).

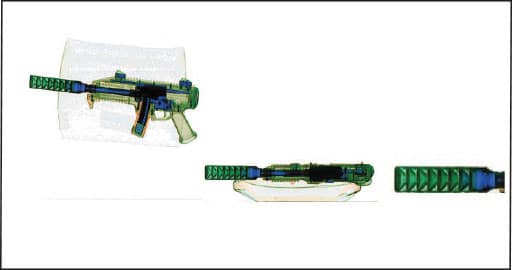

While there is no mistaking this CZ Skorpion as a weapon, the silencer on its own might pose a problem unless the screener is familiar with the image.

Thus it is vitally important that TIP libraries are frequently updated as new firearms, or firearm accessories come into the market.

There are other types of weapons that should be considered in a general transport context. The flamethrower (image shown above) would be a deadly weapon if deployed a confined space. Freight screening system operators are aware of the possibility of Very Large Improvised Explosive Devices such as this 1,500lb VLIED however, at time of writing no TIP library for freight systems exists.

TIP libraries are subject to review by TSA, DfT, and ECAC member countries but this is not applied consistently in many other states where the X-ray system owners rely solely on the manufacturers to install libraries without applying the ICAO recommendation for regular updates.

Conclusion

The ICAO recommendation as expressed in OTAC 178-3, though it refers to purely aviation security, should be followed by all transport organizations that conduct X-ray screening operations. In addition, it is necessary that all TIP libraries are regularly revised for relevance.