The air traffic control recording was chilling: “We’ve got the guy that tried to shut the engines down out of the cockpit…. I think he’s subdued,” radioed the pilot of Horizon Air flight 2059. The Embraer EMB-175 (see graphic 1) diverted to Portland, Oregon, instead of its intended destination of San Francisco. Once on the ground, law enforcement officials confirmed just how close a 44-year-old off-duty Alaska Airlines pilot — Joseph Emerson — came to bringing down a commercial aircraft with 83 souls on board this past October.

Emerson (see graphic 2) was commuting back home and was authorized to ride in the cockpit jump seat like any airline pilot — a common practice in the industry. He made casual conversation with the crew during the flight before suddenly throwing his headset across the cockpit, announcing “I am not OK,” and grabbing the two red T-shaped “fire handles” on the cockpit ceiling (see graphic 3) meant to shut down the engines in an emergency. To fully activate the system, the handle must be first pulled down, which cuts off fuel, electrical power, and hydraulics to the engine. Twisting the handle then releases halon gas inside the engine to smother a fire. One of the pilots quickly grabbed Emerson and reset the handles. The airline reported that residual fuel remained in the lines, and the quick reaction of the crew restored the fuel flow. The crew then subdued Emerson and got him out of the flight deck.

Just four days before this disturbing event, another pilot — Jonathan J. Dunn — was indicted and charged with interfering with a flight crew over an incident that occurred during a Delta Air Lines flight in August 2022. Dunn, who was the first officer, threatened to shoot the captain after a disagreement over diverting the flight to take care of a passenger with a medical issue. Dunn was authorized by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to carry a gun under a program created after the September 2001 terror attacks and designed to safeguard the cockpit from intruders. The Federal indictment stated that Dunn “did use a dangerous weapon in assaulting and intimidating the crewmember.” Dunn has since been fired, and his gun was taken away.

These incidents have renewed the debate about psychological screening of pilots, which initially began in 2015 when First Officer Andreas Lubitz (see graphic 4) locked the captain out of the cockpit of a Germanwings Airbus A320 before intentionally ramming it into the French Alps, killing all 150 people on board (see graphic 5). According to the final report, the copilot started to suffer from severe depression in 2008. In July 2009, and each year thereafter, his medical certificate continued to be renewed. About a month before the crash, a private physician recommended the copilot receive psychiatric hospital treatment due to a possible psychosis, but no aviation authority was informed.

The State of Play of Pilot Mental Health Assessments

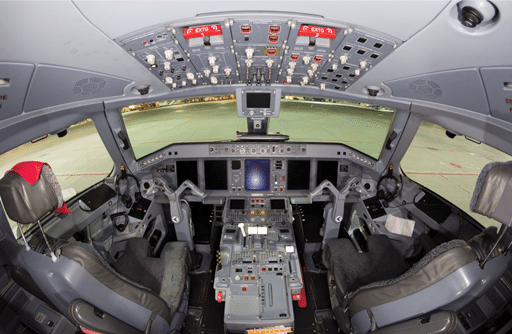

The “insider threat” has always been a significant concern with regard to aviation security. The Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) regulations require airline pilots to undergo a medical exam by an Aviation Medical Examiner (AME) every six months. The AMEs are trained to determine the pilot’s mental health and fitness to fly. While this process provides a means to vet airline pilots, it relies largely on trusting pilots to volunteer information about their mental health.

Pilots are required to disclose during their medical exam any medications they take and whether they have depression, anxiety, drug, or alcohol dependence. They are also required to report any doctor visits during the previous three years and all medical history on their FAA medical application form. This form includes questions about mental health. Based on the answers on the form and the examination, an AME may ask further questions about mental health conditions or symptoms. The AME can request additional psychological testing, or defer the application to the FAA Office of Aerospace Medicine if he or she is concerned that further evaluation is necessary (see graphic 6).

In addition, commercial airlines often have their own mental health screenings and requirements, and they conduct background checks on prospective pilots. Many airlines – such as Alaska Airlines — have also established pilot peer programs to encourage pilots to talk to other pilots about their problems. Apparently, these efforts are not foolproof in preventing these types of incidents.

Previous Events and a Common Thread

Over the past decade, there have been at least seven airline events in which a flight crewmember was suspected of having intentionally crashed the aircraft, or attempted to do so (see graphic 7). Three of these events occurred in the U.S. or involved a U.S. air carrier. When looking further back three decades, these types of events were less frequent, but equally dramatic. Perhaps the most dramatic occurred in April 1994, when FedEx Flight 705 was hijacked by an off-duty jump seat rider. Facing possible dismissal for lying about his reported flight hours, FedEx pilot Auburn Calloway (see graphic 8) boarded a scheduled cargo flight as a deadheading pilot with a guitar case carrying hammers and a speargun. After a bloody battle with the flight crew, the airplane was able to land safely. Five years later, First Officer Gameel Al-Batouti (see graphic 9) intentionally crashed Egypt Air flight 990, a Boeing 767, into the Atlantic Ocean shortly after takeoff from New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport. All 217 people on board were killed.

Security expert Tom Anthony, a former FAA division manager for Civil Aviation Security who is now the director of the University of Southern California’s Aviation Safety and Security Program (see graphic 10), worked on the EgyptAir 990 case, and studied the FedEx flight 705 event. It was no surprise to him when he heard the testimony of family and friends about Joseph Emerson, the pilot involved in the recent Horizon Air flight 2059. The media reported that Emerson’s neighbors were “shocked” that he was involved in the incident, and that he is “a loving husband and father” to his two young sons. Emerson’s wife Sarah Stretch told reporters that her husband, “…never would’ve knowingly done any of that …That is not the man that I married.” She said she knew her husband was struggling with depression but was shocked over his arrest.

“The number one precondition is severe depression,” Anthony explained. He said that each one of us has three personas: (1) the “social self” that we share with the public, friends, and colleagues; (2) the “personal self” that we share only with our spouse or closest family and friends, and (3) our private “secret self,” which we share with no one. It’s that “secret self” that can be difficult to identify.

Anthony says that a probable factor in the rise of these events is the lack of social support. “The internet has had a huge impact … it has led to a lot more time in isolation.” In addition, he says “the internet allows people to indulge in their private side … kind of a “mal-private self.”

He explained that Callaway from the FedEx, Lubitz with Germanwings, and Al-Batouti all had previous incidents “that were ignored or not captured.” All displayed symptoms of depression such as insomnia, unwillingness to engage in normal conversations, and other common indicators.

“We have to acknowledge that mental conditions can be hazards … just another hazard that needs to be identified and mitigated,” he said. “We need to find better ways to “identify behaviors that point to hazards.”

Anthony also believes that the current shortage of airline pilots is another factor that is exacerbating the problem. Pilots that are being hired do not have as long resume with former companies in which background checks can be performed. Also, there has been a marked decrease in the number of pilots that have military backgrounds. There is “less opportunity to know them,” explained Anthony.

Mitigating the Risk of Suicide by Aircraft

The Germanwings tragedy highlighted the importance of monitoring airline pilot psychological health. As a result, the FAA chartered a Pilot Fitness Aviation Rulemaking Committee in 2015 to assess methods used to evaluate and monitor pilot mental health and to identify possible barriers to reporting concerns. The final report concluded that “the best strategy for minimizing the risks related to pilot mental fitness is to create an environment that encourages and is supportive of pilot voluntary self-disclosure.”

The report also noted, “Early identification of mental fitness issues leads to better results.” The committee offered recommendations including the use of pilot assistance programs and stated that when a culture of mutual trust is created, pilots are less likely to conceal conditions and more likely to seek help for mental health issues. This is similar to the work that the airline industry successfully performed in the 1990s to remove the stigma around alcoholism.

To its credit, the FAA responded to the committee’s recommendation on a number of fronts. During the last several years, the FAA has invested in more resources to eliminate the stigma around mental health in the aviation community so that pilots seek treatment. This includes: increased mental health training for medical examiners; support of industry-wide research and clinical studies on pilot mental health; hiring additional mental health professionals to expand in-house expertise and to decrease wait times for return-to-fly decisions; completed clinical research and amended policy to decrease the frequency of cognitive testing in pilots using antidepressant medications, and; increased outreach to pilot groups to educate them on the resources available

The FAA asserts that it is a misconception that if you report a mental health issue, you will never fly again. In fact, the FAA states that only about 0.1% of applicants for a medical certificate who disclose health issues are ultimately denied a medical, and then only after an exhaustive attempt to “get to yes.”

A New Push for Answers

In response to this issue, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) hosted a “Summit on Pilot Mental Health” this past November. The agency’s chair, Jennifer Homendy, has been a vocal critic about the issue. “There’s a culture right now, which is not surprising to me, that you either lie or you seek help,” said Homendy during the forum. “We can’t have that. That’s not safety.”

Homendy called for some form of an amnesty period from the FAA where pilots who have experienced issues can discuss their situation openly without fear of repercussions. “We are all human,” Homendy said. “Who hasn’t among us faced some sort of crisis in our lives? We expect pilots will be some superheroes and continue on as if nothing’s happened in our lives … Everyone is in need of help at some point.”

The day before the NTSB Summit, the FAA announced that it was appointing another Rulemaking Committee to examine pilot mental health “to provide recommendations on breaking down the barriers that prevent pilots from reporting mental health issues to the agency.” The committee will include medical experts and aviation and labor representatives, and will build on previous work the FAA has done to prioritize pilot mental health. In addition, the FAA will work with the committee to address open recommendations from a July 2023 audit report from the Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General (OIG) regarding pilot mental health challenges.

The DOT OIG report confirmed that the FAA’s ability to mitigate safety risks is limited by pilots’ reluctance to disclose mental health conditions. Primary factors that discourage pilots from reporting are the stigma associated with mental health, potential impact on their careers, and fear of financial hardship.

The DOT OIG report also asserted that it is imperative that the FAA continue to address barriers that may discourage pilots from disclosing and seeking treatment for mental health issues. Also, a continued focus on this issue from the FAA and industry stakeholders could improve mental health outcomes for airline pilots and enhance the FAA’s ability to mitigate safety risks.