The airline landscape has grown increasingly diverse and sophisticated in the last few years.

The neat divide between the full service legacy carriers, that offer connection flights, and the much simpler, point to point operations embraced by the first generation of low cost airlines is getting increasingly blurred as business models hybridize.

Interline agreements have long been a staple of the air travel industry. Basically, airlines partner with one another to offer passengers a seamless journey across their respective networks, from point A to B through some intermediate transit point.

This type of collaboration traditionally took place within an established formal framework, such as those represented by the three major airline alliances or the myriad of bilateral agreements that exist between carriers, but there has always been a segment of travelers ready to self-connect, at their own cost and risk, whenever conditions are right.

That is, if fares are low enough, many will put up with the inconvenience of having to go through the whole airport sequence more than once. Self-connecting requires collecting your bags upon arrival at the transit airport, checking them in again and often enduring extra queues and security controls, not to mention the chances of getting stranded along the way if one of the flights in the itinerary gets cancelled or delayed.

Online aggregators and OTAs such as Kiwi.com took notice and, about a decade ago started catering to this, apparently underserved, market by showing in their search results itineraries combining flights from multiple low cost and non-aligned airlines that before that could only be booked separately. In fact, even if Kiwi lets you book them in one go, as far as the airlines are concerned, these itineraries would still be made of two separate bookings.

What aggregators bring to the table is visibility, showing you all the different options in one place, and the ease of use of being able to book them all through one single interface. Some of them also issue a guarantee that, in case one of the connections is missed, they will take care of you, so that you don’t find yourself stranded.

Besides the operators that, like Kiwi, are known for their B2C focus, a whole crop of technology companies emerged to target primarily the B2B market, helping airlines, airports and other travel operators link the dots without the need to embrace the legacy interlining framework and its complexities.

Firms such as Air Black Box, Dohop, Airsiders and Tripstack have all been developing software platforms to propel this type of “alternative” connectivity that has come to be commonly known as “virtual interlining”.

But how do these firms combine trips booked on multiple stand-alone airlines? And what are the implications for passenger data management and the transfer of personal information to all the relevant parties, including air operators and government agencies?

Tradition and Innovation

First of all, let’s have a look at what happens with traditional interlining.

Most traditional interlining takes place within IATA frameworks, such as the Multilateral Interline Traffic Agreement (MITA), which establishes a whole set of rules and parameters for inter-airline cooperation, from technology standards to the settlement of payments through IATA’s own International Clearing House (ICH).

This whole system relies on a rather old setup (the EDIFACT technology used for data transfers dates back from the 1980s!) and it can also be quite expensive as well, with multiple layers of fees and charges.

In return, those airlines that are already part of the system benefit from a well established mechanism capable of offering a rather seamless experience to the passenger.

Whenever you are looking for flights between two destinations, a simple search on an airline website or through a travel agent (online or offline) would send a query to the GDS or directly to the airline PSS (Passenger Service System).

These in turn will pull flight options from their own inventory or from schedule databases (like those collected by OAG and Cirium) as well as the related pricing information (most likely from ATPCO) in order to suggest possible itineraries (note, however, that the options on offer may not include all possible operators and flight combinations!).

Once the flight is booked, a single Passenger Name Record (PNR) and an e-Ticket is generated for the whole itinerary.

The PNR, whose identifier is the six-digit code that you receive when completing a booking, acts as a repository of information, not just for the operators involved in the different stages of the flight, but also for those governments and security agencies that require getting passenger information in advance.

Although a PNR can technically include hundreds of data points, the EU authorities require access to at least 19 data items pertaining to five different major categories: passenger data, flight details, payment status, boarding status and seat and baggage information. Access to these records helps authorities check the incoming passengers lists against their own law enforcement databases and flag any suspect passengers in advance.

In America, the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has a similar requirement, also requesting airlines to submit PNR information in advance of any incoming flight to the U. S. (and since a 2011 agreement, the EU also shares PNR info with the U. S. authorities). The required passenger data is transmitted through a messaging standard called PNRGOV.

What happens, though, when a traveler’s booking is, in fact, a virtually interlined flight with several independent legs involved, each flown by a different carrier, but combined to create a unified itinerary?

“We create a super-PNR that identifies the whole journey from beginning to end, even if there are two or more airlines involved” explains Peer Winter, VP Commercial Business Development at Air Black Box, a firm, now part of the 777 Travel Tech group,

What systems such as Air Black Box do is create a sort of synthetic identifier showing the entire journey, what many in the industry call a “Super-PNR”, which makes it possible to orchestrate other products and services into the same record.

Air Black Box

This Super-PNR supplements the individual PNRs of each individual leg of the journey and the passenger and operators can use it to identify the itinerary as a whole.

However, this super-PNR exists for mere informational purposes.

In order to block inventory and for other practical and operational needs, each of the airlines involved keeps in its PSS the active booking for the specific leg of the trip it is responsible for, as well as the related PNR.

When the relevant authorities request that passenger data be submitted, each of the airlines would send the info that relates to the specific flight segment it is taking care of, just as it would on any other passenger, regardless of whether that traveler has interlined with another carrier on that trip.

Similarly, each airline is responsible to provide customer service during its leg of the trip only.

The aggregators, however, insert data into the super-PNR, so that administrators at all the airlines involved can see the relevant details for the whole journey.

For example, Air Black Box adds information to the Super-PNR when it is of significance for its ThruBag process, a service that allows for baggage transfers in multi-airline itineraries. In such cases, the added information is forwarded to the DCS system (Departure Control System) of the respective airlines, allowing them to print an interline bag tag.

It is also possible to use virtual interlining to connect carriers that do not have any agreement between them. In fact, an increasing number of airlines and airports are deploying this technology pro-actively, in order to open new commercial opportunities beyond the reach of its own network.

Easyjet and Norse Atlantic, for example, are two examples of low cost airlines that have assembled a small number of partners, most of them other LCCs with some degree of geographical complementarity, to feed their respective networks.

In both these cases, the virtual interlining “plumbing” has been the work of Dohop, an Icelandic tech firm that has carved for itself a relevant role in this market and has since also expanded into adjacent markets, such as air+rail connections (it services, for example, the connections between Easyjet and the German railway operator Deutsche Bahn).

Why is Virtual Interlining in Fashion?

Low cost airlines are, thus, deviating from what was long considered one of the core tenets of the LCC orthodoxy: avoiding the operational complexities of managing flight connections.

However, connecting flights are often unavoidable and here is where the new generation of interlining tech may have an important role to play. Airlines are outsourcing the complexity to those platforms in order to get additional revenues and optimized load factors in return.

“It is not just that traditional interlining uses old and clunky technology, it can also be quite costly compared to the API-based platforms of the virtual interliners. Payment settlements, for example, are really quick, whereas in the legacy system they can take weeks or months” explains Ann Cederhall, an airline distribution technology expert and consultant at LeapShift, a firm that advises companies in the travel industry.

T2Impact

“IATA has been trying to fix interlining for ages but failed many times. Basically, because its vision is too restrictive. The demand for interlining of any type has increased because of the reduction (since the pandemic) of the number of nonstops,” thinks Timothy O’Neil-Dunne, who co-founded Air Black Box and is currently a principal at T2Impact, a consultancy firm providing advice to the aviation and travel industries.

Virtual interlining has become particularly interesting for the smaller, independent airlines. Why so?

While large legacy carriers can offer hundreds or thousands of destinations throughout the world, either on their own or through their alliances, airlines with small networks or limited geographical reach may be leaving crumbs on the table when hard-won traffic gets to their websites, but can’t find what they are looking for. AirAsia, for example, may sell you a ticket on another airline if they don’t fly the route you are looking for, even if there is no formal alliance of any sort with the carrier in question.

Solving the Baggage Problem

One of the major friction points that hasn’t been fully sorted, though, and makes virtual interlining a tough proposition for some segments of the market is baggage handling.

It may not be an insurmountable issue for a significant number of passengers, though. Business passengers, people travelling on their own…the introduction of basic, handbag-only fares by low cost carriers such as Wizz Air or Vueling, shows that many passengers can do not just without checked-in bags, but even without cabin ones.

With SITA’s 2022 Baggage IT Insights report, pointing to the fact that 40% of baggage handling incidents were connected to interlined journeys, perhaps it is not a bad idea for virtual interliners to stay away from this activity.

Despite the well-known shortcomings, baggage is one of the elements that traditional interlining is perfectly able to handle at scale and there is a well defined procedure that minimizes the number of touchpoints for the passenger. Many legacy airlines subscribe to a protocol called Inter-Airline Through Check-In (IATCI) that makes it possible for passengers and bags to be checked in only once, at the start of the journey, when on multi-airline itineraries. However, this is not the case for most low cost carriers.

If baggage-handling remains a hard nut to crack it is not for lack of want, though.

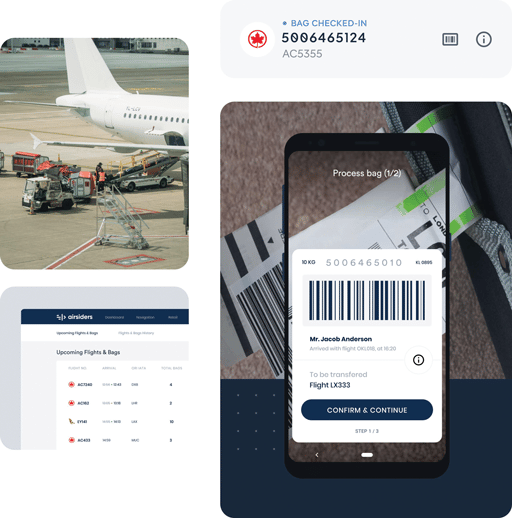

Both Air Black Box and Airsiders have been working on baggage handling solutions for interlined travelers, although these systems have seen a rather limited deployment so far.

Airsiders, for example, is marketing a bag transfer solution for which it expects to get a patent soon. Little public information is currently available about this system, but it is worth noting that Airsiders is linked to the Beumer Group, a large German manufacturer of ground handling equipment, so it is no stranger to the business of baggage handling.

Air Black Box, in turn, offers its own (previously mentioned) ThruBag solution, which it introduced in 2021 and is already being used by two small airlines in Africa, Lift and FlyNamibia.

Its implementation requires some compromises when it comes to the “virtuality” of the whole process, since in this case it is necessary to have some agreements in place, between the airlines involved as well as with the handling operators.

Operating an interlining system with bags on a truly global scale requires boots on the ground as well as the use of a unified PNR for the whole itinerary.

What’s Next?

The rise of virtual interlining hasn’t gone unnoticed.

IATA has got the memo and it is working on a new interlining framework of its own: the Standard Retailer and Supplier Interline Agreement (SRSIA), which is expected to be closely aligned with the OneOrder initiative.

Long in the making, One Order is a key IATA initiative that aims to move away from concepts such as “ticket” and “PNR” and move towards a new concept called “order”, something more akin to a shopping basket, which contains all the passenger’s trip transactional information.

The “order” will facilitate the addition of multiple services and ancillaries. Also, whereas PNRs are purged when the last trip activity is completed (and the PNR record locator is recycled), an order is not purged and allows users to retarget consumers based on past activity.

The ability to boost the airlines’ retailing capabilities is, thus, one of the major drivers behind this project, whose goal is to eventually replace the PNR entirely.

Travel Consultant

“Think of the typical Amazon shopping basket to which you can easily add all sorts of products and services. At the moment, for example, you can interline, but it is difficult for airlines to sell ancillaries on each other’s flights” explains Ann Cederhall, using the analogy with the retailing giant.

In fact, on SRSIA, rather than talking about different types of carriers, the marketplace revolves around the concept of “retailer” and “supplier”, an appropriately ambiguous terminology that further blurs the distinction between who buys and sells what within the air transportation ecosystem.

But this is, perhaps, a topic for another day.