I love my work. Aviation security is a fascinating field to operate in. And to top it all, it has taken me to the most wonderful places on Earth, places that it is very likely I would not be able to visit otherwise.

In recent years, I have been travelling quite frequently to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo Kinshasa, sometimes referred to as the DRC). The DRC is probably the most intriguing and complex country in Africa, perhaps in the world. While located in central Africa, it stretches to the west up to the Atlantic Ocean, and in the east all the way to Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania. Of the countries in Africa, only Algeria is larger in size. DRC is so big that it is practically impossible to cross Africa from north to south without passing through it. More than 200 different ethnic groups live in there, speaking hundreds of different languages and dialects.

The DRC is also one of the poorest countries in the world, although it is endowed with vast amounts of natural resources (it is the home to most of the important minerals on Earth, including cobalt). With the installation of a government in 2003 by current president, Joseph Kabila, economic conditions began to improve; the government revived relations with international financial institutions and international donors, and President Kabila began implementing reforms.

Unfortunately for the DRC, it is also the place in which nine Ebola outbreaks occurred. The recent outbreak consists of more than 30 confirmed Ebola cases. A similar number of cases are, as I write, still under investigation.

The Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) was first discovered in DRC, near the Ebola River, 42 years ago. It is considered a virus that originates in animals (especially monkeys) and is passed on to humans. The EVD induces fever, reduces blood pressure and causes organ failure. And it is lethal. Once infected, patients have a very low chance of surviving.

Besides being extremely dangerous, Ebola is easily introduced to humans just by close contact with blood, organs or other bodily fluids. The ease of contagion has severe consequences for mass public transportation systems, and especially the aviation industry. One infected human arriving at an international airport can lead to mass infection that will get out of hand and spread all over the world.

“…the quick response of the Congolese Government, as well as the trained Congolese crews, the detailed emergency procedures and protocols, and the immediate support of the WHO saved many, many lives…”

Therefore, it is critical that upon the identification of a new Ebola outbreak, the relevant authorities act swiftly and diligently to contain the spread of the virus by sealing off the area and preventing traffic through it. The DRC is probably (as a veteran of eight previous outbreaks) the country most prepared to react to epidemic viruses. Indeed, in recent months I have witnessed the swift response to the new Ebola crisis of the Congolese authorities, together with the World Health Organisation (WHO). President Joseph Kabila managed to arrange $4 million (approx. £3 million) for the emergency response; the US added $7m (approx. £5.2m) to the pot.

In a conversation I had with the DRC Minister of Health, he explained that the first signs of a new outbreak of Ebola occurred in the Equateur province, in the area of Bikoro (in close proximity to the big urban centre of Mbandaka, a city of around 1.6 million people, and less than one hour’s flight from Kinshasa). The medical teams arrived on site quickly and promptly started to identify all the entry and exit points in order to circumscribe a closed area. They identified the borders of the infected areas and the contiguous bordering areas, and specially equipped teams were dispatched to these sites. Special attention was given to the local airport, as well as the public bus system.

“…Mbandaka Airport, as well as the main international gateway airport in Kinshasa, were immediately manned with teams using laser thermometers to check for fever in all outbound passengers…”

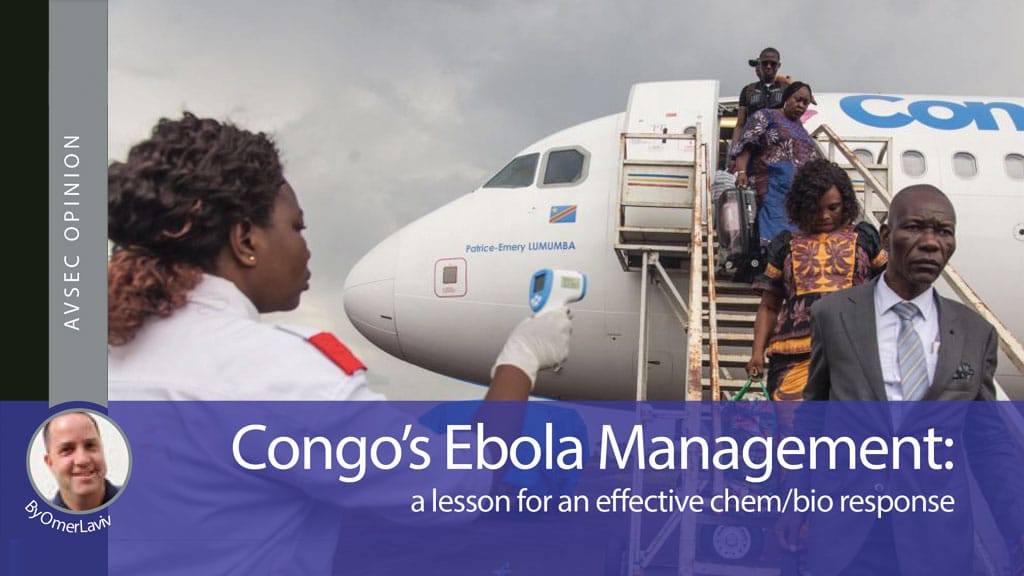

Mbandaka Airport, as well as the main international gateway airport in Kinshasa, were immediately manned with teams using laser thermometers to check for fever in all outbound passengers. Gradually, the Congolese authorities delivered teams and equipment to all the other DRC airports to ensure that all departing passengers were checked prior to boarding.

It should be made very clear: the quick response of the Congolese Government, as well as the trained Congolese crews, the detailed emergency procedures and protocols, and the immediate support of the WHO saved many, many lives. And not just Congolese lives. Indeed, if we compare the 2018 outbreak to the previous 2014-2016 outbreak, we can see how professional and efficient the 2018 reaction was. In the previous outbreak, Ebola had spread to countries like Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, which found themselves unprepared to deal with the complex nature of the virus; nor were they able to handle the sheer quantities of patients or offer aftercare to victims’ families. More than 11,000 people died.

Before I boarded my flight from Kinshasa to Brussels (with my body temperature at a normal 36.8 Celsius) I could not but ponder a biological terror scenario. How prepared are our governments, let alone our airports, to manage a bio attack? A chemical weapons attack would be bad enough, but the SARS crisis demonstrated the longevity of the impact of an infected society and the need to rapidly implement measures to contain a disease. Yet how many airports have developed contingency plans, let alone tested them, as a result?

“…more than 11,000 people died…”

The DRC knows that a further Ebola outbreak is a distinct possibility and, whilst hoping for the best, has planned for the worst. We need to learn from the DRC’s experience in order to be prepared for the horror of an act of biological warfare. After all, it is also a distinct possibility and arguably just a matter of time.